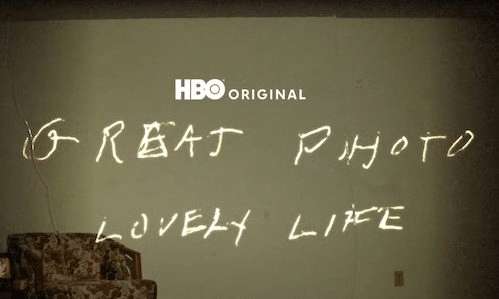

Seriously impactful documentaries are made every year but once in a while, I find one that hits me so hard I have to share it around, dive deep into it, and encourage as many people as possible to watch it. Amanda Mustard’s Great Photo, Lovely Life is one of those landmark works. It blew me away at this year’s Tallgrass Film Festival and will impact every viewer on a visceral level.

I walked out of my screening weak at the knees. Afterward, I sought out Mustard to sit down and talk about her film. We had an incredible conversation that led to an even deeper grasp of the scope that she wants to shine a light on.

The following interview contains discussions of pedophilia and sexual abuse. It has been edited for length and clarity (both Amanda and I say “like” far too much).

————————————————————————————————————

Clint: I kind of want to start light and just talk about your move from photojournalism to documentary.

Amanda: Sure. Also, you don’t have to protect me if that’s a stress that you’re carrying. I’ve been able to make this, so I’m pretty good.

Clint: This is information I was interested in anyway because you were a photojournalist and you still are, but you did this as a documentary. There are a lot of different ways this could have been tackled in several different mediums. It would have made a solid photojournalism project. It would have made a good narrative if you wanted to go in that direction. It would have made a good book. What brought you to the documentary?

Amanda: I started this as a photo project. So I started photographing when my grandmother was dying and then I photographed a lot of my grandfather when we went down and like take her ashes down. And at the time I was imagining, okay, I knew I wanted to interview him and just kind of be like, “Dude, what the fuck is going on in his family? Like, what, are you okay? Like, what happened?” And he…that interview was so insane and unexpected.

Clint: That would be the one you opened the documentary on?

Amanda: That was the first thing I ever filmed. It was because I thought I was going to lay audio over the top of a photo slideshow, which was very popular in photojournalism at the time. And then once I had the interview, I was just like, “This feels bigger and makes me want to ask more questions to more people”. And I had no idea what I was doing. And it actually took me two years of just kind of being like, “I know I want this to be a film,” and I kept filming stuff. But I don’t know what I’m doing, “Can someone help?” I had done a hostile environment training course for conflict journalists and Rachel Beth Anderson was a wonderful woman in that group. This actual group of friends had raised $2,000 for me and like handed it to me at a diner and were like, “We want you to keep working on this project.” So they were my original core investors and Rachel was one of them and someone said, “Hey, why don’t you ask Rachel for help? She’s a fantastic cinematographer and filmmaker.” She was trying to help me for probably like a year remotely and then eventually she was like, “Let me just come to you.” And that helped me because it’s just too much to think about. It’s too much to think about the technical side, when it’s not my wheelhouse, along with the emotional side. So yeah, we just started working on it together. and spilled it out. It’s not like there was a particular plan. I lived in Thailand so I would fly back a couple of months of the year, absolutely drain myself doing it, and go back to my home on the other side of the planet. You can go either way. It’s the same distance. I really needed that distance. And the reason I eventually moved back was because of the pandemic, I couldn’t fly back and forth. So I was like, okay, shit, I’m gonna have to go back to my hometown. And I just felt it was important anyway, like to be immersed in the community and available to my family and for the edit process.

Clint: You touched on something that I did want to talk about, which was your prior level of awareness. So you kind of knew that there was something really fucked up in the whole thing, but not exactly what? Were you just too young, maybe pulled away from your grandparents?

Amanda: I will say that I was born two years after my grandfather left the state. So that is like the only thing; it was just luck.

Clint: That’s how you got away from it.

Amanda: Yeah, yeah. And I mean, I do have some memories because he still was around. He’d stay at our house when he came and visited, which is also insane. But yeah, like there was some… there weren’t hard memories that I had, thankfully. And actually, through this process, my cousin reminded me. She was like, “Oh, you told me something that I didn’t remember.” And that was a scene that was cut from the film of my processing. Brains do amazing and also terrifying things to lock this shit down. So, um, can you remind me of the question?

Clint: Oh, just like the level of knowledge that you had when you started going into this?

Amanda: Sure. Um, I kind of always knew. Um, there wasn’t this moment that it was like, whoa! Uh, it was very normalized in my family. We joked about it.

Clint: Like creepy grandpa or something?

Amanda: Yeah, like, oh, it’s Girl Scout season, better watch out for Grandpa. Like, that was a common family joke. That was just the culture of it. And I was also raised very evangelical, so there was a lot of “pray it away” energy. The phrase that I learned that is very helpful is “spiritual bypassing.” And I do think that there are a lot of tenets of people’s faith that can be very helpful in coping with these things, but the, “I can’t, I have to just hand it to God,” or, “Just like pray that something will change,” is enablement. You know, it’s a part of the problem. So yeah, I kind of always knew and it was just casual and jokey in the family. It wasn’t until I had gotten a little older and experienced my own sexual assaults, which I had to lean in on and face and deal with. And it was in that process that I learned the language around rape culture and the patriarchy. “Oh, actually what happened to me was rape?” Like it wasn’t my fault and all that. And just kind of by osmosis in that process, I started looking at my family like, “Whoa! You know, like what? None of you have actually talked about this.” I just wanted to kind of check in with everybody. And I mean, people were pretty open about it. Not everybody wanted to be a part of the film and some people do not want to talk about it. Nobody was against me doing this. Even if they didn’t have the capacity to be a part of it.

Clint: It says a lot that no one was against you doing it.

Amanda: Yeah, they said, “I’m glad somebody’s doing it.” I heard that so many times. Even if they were like, “I can’t talk about it.” I mean, it was overt. It was very…I don’t even understand how, like, my mom and her brothers…didn’t know the amount that they did. I mean one of the opening scenes of the film is her and I. One of the first things we filmed with my co-director, Rachel, we asked, “What do you remember?” And it’s so interesting that they remember details like, “Oh, I got bullied at school and harassed because of this.” I asked, “Well, what happened?” She’s like, “I don’t know.” I don’t know if that’s a mental block or if they really didn’t know. Like why did they say this to you as a kid when you were in high school? Why did the football team come up and say, “We’re gonna do to you what your grandpa did that kid?” They knew. And I think that – and this is something I have to be very, very delicate about – if you’re someone like my mom who has had that much trauma through your life that’s never dealt with it develops a lot of issues. And then you escape that by entering a wildly abusive marriage. You just run from it and then that’s how she met my father. Where were we?

Clint: We were talking about dealing with that level of abuse and repressing it and then not entering a bad relationship.

Amanda: This isn’t like a judgment, it’s just kind of the facts of her life. She was always living in this reactive place of survival and didn’t have good options or choices to make. That just kind of compounded and then you have me and in my early 20s, how many years after? You know again she was in her early 50s when we started to ask really hard questions. There’s a backlog and because of her faith and her own personal ethos she doesn’t want to deal with it in the same way I would hope that she would and that I have to just kind of respect that. I don’t even know what the answer was.

Clint: That was kind of perfect and it led to several other things I was going to get into. The religious aspect of it. I grew up highly evangelical as well. My family was Seventh-Day Adventist.

Amanda: My condolences.

Clint: Yeah, there’s a lot of, you know, let it go, pray it away, give it to God, forgive them even if they won’t give you the condolences.

Amanda: Compulsory forgiveness.

Clint: I think that perpetuates the culture of it.”That’s fine, we can just be forgiven for it, it’s okay.” And that kind of has led to, especially amongst men my age, this kind of crisis. Because I went completely atheist around eight or nine and I just didn’t admit it to myself until probably mid-20s. But I mean that moment where you realize there’s no one to give anything to, when you fucked up you have to go make it right, it’s accountability. And that stuck with me that [your grandfather] had no accountability. And even right up until the last moment, the last time you guys saw him, he was making lewd comments and passes at your co-director. And then he was confronted with it and he just didn’t want to hear it, and he didn’t want to respond to it, which I think almost is…I don’t know if he saw it as a willful cruelty, but it is a willful cruelty.

Amanda: I think that my grandfather’s got some serious psychopathy going on. I’m not a psychologist. He never got a diagnosis, but that’s kind of the problem. But based on my research and my understanding of him, he checks a lot of boxes – the lack of empathy, the manipulation, the kind of charisma, the self-aggrandizing.

Clint: It’s cult leader. It’s cult leader-esque.

Amanda: For sure, for sure. And I’m not even sure how much of it is about the pedophilia tendency as it is power. He wasn’t exclusive to children. It was children and their mothers and women and there were boys that he implicated in the abuse his work held.

Clint: See, and that’s what I wanted to get into a little bit because the documentary primarily focuses on his targeting of young girls.

Amanda: Yes.

Clint: Because that is… It seemed to be his primary desire, but there were also, again, young boys, mothers, women. So this was more than just one group. This was a larger, wider, all-encompassing thing.

Amanda: And I mean, I can…It was a tough legal thing to…there was…I mean, the legal journey of making this film at an HBO level. It’s like…we couldn’t say a lot. for liability, which is fine. There’s already so much to say.

Clint: It’s a lot and if we need to cut anything…

Amanda: No, no, no. It’s totally fine. But he did, you know. I think that I think that this is fine to share. One of the things that my uncle had shared in his interview, something that didn’t make it into the film, was that when my grandfather was in court he had a very Larry Nassar moment. He was trying to do a demonstration in the courtroom of why a medical procedure was for chiropractic care and not abuse, which is exactly what Larry Nassar did. And my uncle was there when he was 16 or something. He wasn’t really sure of the context, I don’t I don’t know if it’s suppression, but [my grandfather] demonstrated on his son. You know this very grotesque-ass…like it’s such a gray area that I don’t think my uncle sees it as that. There were so many ways that he would, I don’t know, that’s like a very gray area kind of thing, but it is [sexual abuse]. It is. So it wasn’t just girls and there was a lot of young boy that he would also get involved with the girls. We did not want this to be a film about what [my grandfather] did, so we weren’t going to sensationalize it. We really, really intentionally toned that down. But the fact of the matter is it was not just girls. I think that is important to know. And I think it was a power thing. And then when he got older, it became older women, too. He was continually kicked out of places. And my mom and I even tried to report things that we knew he was doing. I had photographic evidence of stuff and nothing was done. So it was kind of like whoever was in his grasp, whoever was accessible to him, it was this like exercise of power.

Clint: See and I read the whole thing as more of a documentary about accountability and the lack thereof within… not just his generation and going back but within everybody who like, coldly tries to ignore it or to step away from it. But he did focus on the young girls and that doesn’t surprise me because… There’s a long-standing fetishization of youth in women. There’s the famous Rolling Stone Lindsay Lohan cover. She’s 18 now. There’s the Natalie Portman and Emma Watson countdowns.

Amanda: There’s Lolita.

Clint: There’s Lolita, which has gone from being sort of a parody but yet also a fetishization of pedophilia. There’s tons of this kind of stuff. It’s everywhere. I grew up the same age as Mary Kate and Ashley Olsen. And it was real strange to me to have family and family friends in their late 20s and 30s and 40s who are like, oh, they’re 18 now. And that’s like, no, you’re not going to go bang Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen. That’s not going to happen. But the fact that you can, legally, without getting in trouble if they consent, is something that you’re getting off to. I don’t understand that. I’ve never understood that.

Amanda: It’s a good thing. I thought about that a lot. It’s like, well, it’s good that you don’t. I’ve spent a lot of time in this filming, like, I don’t understand. But it’s like, no, that’s a good thing.

Clint: Yes. If you felt that, you should. probably talk to somebody.

Amanda: Exactly.

Clint: When you find somebody who’s 18 attractive when you’re 18, 19, 20, that’s one thing. When you’re 35 and I look at 18-year-olds now I’m like, “Aren’t you supposed to be in school?”

Amanda: I know, I know, I know. This is part of kind of the impact that we want to drive. It’s not like an inherently impact-driven film. It’s a mirror that people can find themselves in. It was made to be projected on and not tell you how to feel. But there’s a lot of impact we want to do on child sex abuse prevention specifically. It is a preventable issue. It’s a preventable problem. There are public health approaches that we can take, it’s just that we are in a society that focuses on punishment. And because it’s so stigmatized, because we have a really hard time talking about this without just blinding rage, the hatred is not productive and it’s actually causing more harm. So it’s one of the reasons I made this film was I wanted to humanize my grandfather because it’s the only way we can talk about this and know what the issues are. One of the interesting stats is that our understanding of pedophilia and child sex abuse and the language we use is so misguided. I think it’s like 70% of child sex abuse cases are inflicted by kids under 18. It’s kid on kid. And that comes down to a lack of sex education, a lack of, you know, there’s a number of things that can address this. But we think that there’s all these dudes creeping in bushes ready to pounce.

Clint: There are 40, 50-year-old men creeping in bushes.

Amanda: Yeah, we really just need to understand what we’re actually dealing with if we want to be productive about it. And one of the most important things is you gotta look at them as humans because they are. We have to stop using language, dehumanizing language like “monster.” It’s satanic and it’s, you know, he’s got the devil or he’s demonic or whatever.

Clint: The word pedophile has lost all meaning, especially over the last, I’d say, six, seven years or so. It’s completely been destroyed.

Amanda: Yeah, yeah. And so, and professionally, there are big moves to start. It’s just like, “No, this is somebody who has an attraction to young children,” and being a pedophile is just a descriptive word anyway. It doesn’t mean that they’re abusing or anything like their language is so important.

Clint: They can have that proclivity and not act upon it or seek help for it.

Amanda: There’s a lot of people that want help and don’t want to be doing this and don’t want to feel these things. And we just have created this environment in our society where we don’t let them ask for help. It’s dangerous. And I would encourage you to listen to our producer, Luke Malone, who’s one of the most fantastic journalists on this specifically. In 2014 he did a This American Life piece called “Help Wanted” and he followed young, self-identifying pedophiles, under 18, for a year and a half in their quest to try and get their own support. Therapists would call the cops. How are they supposed to get help? And so they kind of formed their own network/ They call themselves VirtuPed, it’s like virtuous pedophiles. They all have a pact that we will not abuse and will support each other in curbing these urges. So they’re having to do grassroots efforts to kind of find help. So I really hope that this film can generate a conversation that helps us get in that direction of a more productive, prevention-based understanding of the issue.

Clint: I’m hopeful. I’ve lived a lifetime waiting for people to just merely accept that we can have mental health services without it meaning you’re crazy, you’re dangerous. Just because I want to seek mental health doesn’t mean I’m going to hurt myself or someone else. Depression is an actual thing, anxiety is an actual thing, we can’t help these things and this is another thing that eventually we’ll have to remove the stigma from so that we can assist with it.

Amanda: Yeah.

Clint: We talked a little bit about projection, and I’m going to switch tack just a little bit here. Talk to me about the wall projections.

Amanda: Oh yeah. It’s part of the structure. It’s my favorite part. People don’t ever ask about the craft side of it. Those were the most exciting parts to shoot.

Clint: I loved that so much.

Amanda: Thank you!

Clint: I want to know about the room. Where was the room that you did that in?

Amanda: Yeah, so, I mean, early on in the film process, you know, I was, I did this independently for six, seven years-ish of the eight, nine-ish. And I had a lot of creative opinions on this. I mean, I do. I’m somebody who cares deeply about aesthetics and the intention behind the choices that we make. And I never want to make a film that just has an archival photo land on the screen. And my grandfather and his father were hobby photographers so I had 27,000 stills from their archive and dozens of hours of reel-to-reel footage and VHS footage to play with. And that was the most exciting part for me creatively because the footage was, I mean obviously some of it is very disturbing, but it’s also stunning. These photographs…as a photographer myself, they’re beautiful photographs and I was just excited to…

Clint: There are very lovely structures in there.

Amanda: I just love…I just really wanted to, you know, work with them. So I kind of find my collaborators by just like fan-girling work that I love. I saw My Dead Dad’s Porno Tapes by Charlie Tyrell. and I was obsessed. I was like, that’s the tone. Having that levity combined with the heartfelt seriousness of everything, the humanity of these things, because I always want there to be levity. You know, I don’t take myself too seriously and I try to thread that needle with humor when I can. So yeah, I reached out to him and he was super excited. He and his writer, Joseph, drove down from Toronto and we had a double date with me and my co-director. We pulled the archive out and spent a couple of days just talking about things. It was actually Charlie who saw, the back of one photo that said “Great photo, lovely life.” And he said, “That’s a title, dude.” The title was a really hard thing because we didn’t want something corny or telling or sensational. I kind of like that it’s vague and gets into the idea of the delusion that we kind of keep for ourselves and our families with secrets. It went really well and Charlie and Joseph just waited until we got funding. We rented a house in Toronto and we used all the rooms as studios. We wanted it to be…you know, so much of the film is shot in these domestic spaces, and they’re not my spaces. They’re more the demographic of my mom and my sister. So there’s this very kind of like American, slightly “Live, Laugh, Love” energy. We wanted to find a house that just felt like the house that we’d all been in. In America.

Clint: Your grandparents and uncle’s house or aunt’s house. Grew up in this house. Something like that.

Amanda: Yeah. So we wanted something really relatable. There were so many ideas that we had that we had to reel back in tonally to just be like okay. We have to listen to what the film needs and we can’t just go crazy

Clint: Bug nuts with the creativity on maybe this certain type of film.

Amanda: I know, I know, but it was very hard for me because that’s who I am as an artist. So I needed, that was the good balance where like my co-director is, like she shot for PBS Frontline for years and like understands like the weight of these things and she would, she was a great balance to me being a little too normalized and like slightly out of, not out of touch, but like I just deal with this very differently because of my experiences. most people do. So she was kind of the like, I represent normal society.

Clint: I represent people not normal.

Amanda: Yes, yes. And it was an invaluable partnership on that front. So yeah, I went up and there were, I can’t remember how many people on the team, it was maybe like 15 people? And they’re some of the best stop-motion animators in Toronto. They’re all up there, I swear to God. It’s just like the hub of the world’s best stop-motion animators. And it was fantastic for a whole week. Two weeks? One week? I gotta check that. I think it was two weeks. Yeah, we just like…all existed in this empty house and yeah they did projection mapping in different kinds of spaces. We didn’t want it to feel like we were in Grandpa’s house and some people think that but it like doesn’t really matter. We just wanted it to not leave that domestic space when we go back in time because that’s the thing. It’s still here with us so we wanted to keep it really tactile.

Clint: There’s a specific video clip that you keep returning to and babies by its chest and kind of flying it around. And that one keeps repeating particularly in that projection in the room. And there’s a… It’s not sinister, but it also, in the context of the whole thing, it feels uncomfortable. And I think the structure of the room just as a, like, this is everywhere that you’ve been. Everyone has been here at some point. I have a relative who used to…hm…he was always great with us, but the girls in the family kissed him on the lips. And, yeah, I don’t think it ever went farther than that, but that’s there. It’s one of those things that’s just, ah, I don’t know about this. [This documentary] shows that this is everywhere and in every home, whether it’s in your immediate environment or not. The structure of that and then the photo shuffle that you do throughout the film was very fascinating. The photo shuffle is lovely and the wall projection is lovely, but there’s always an undercurrent to it.

Amanda: For sure, and that’s been a really interesting personal and creative journey of mine. I’m actually…this started as a photo project and I am working on a photo book. that says something different. I’m working on a couple of projects and creating this Great Photo, Lovely Life universe.

Clint: I’ll be buying the photo book.

Amanda: Nice, I’m stretching all these muscles because there’s something so fascinating about having these photos and I have this certain relationship to the photos and I’m also a photographer, I have this critical eye. And there’s just something because my family wasn’t talking about it, it was this archive that I felt like maybe I could find answers in. But then there’s the whole kind of like theory of “the photos that we choose to take, what we choose to hide, and they all felt like, oh my god, this is Americana.”

Clint: This is the definition of Americana.

Amanda: My great-grandfather was very wealthy, big fish in a small pond. He invented the Zippo lighter. And my grandfather was kind of raised around that privilege and that power, so they had these incredible visuals. But you’re looking through it, and you’re just kind of like, you see these little things, through this very disturbing element of this, and it’s just a fascinating exercise. You don’t really know what to think when you’re looking at them. And that’s the whole purpose of the photo book. Actually, it’s like looking through these seemingly perfect photos, and the more that you learn, you kind of go back, and you’re like, what was happening here? And then sometimes there seems like, oh, there’s a clue. But if you don’t look close enough, you’re not going to catch it. And you can choose whether to look closely or not. The process of looking at these photos feels very symbolic of the issue at large and how people actually dealt with that, do you actually want to look?

Clint: Well, I do think, like, how close do you actually want to look? The things that we don’t choose, the things that we choose to hide, that is the definition of Americana. No more so than right now, because we’re talking about eliminating things like CRT from schools. Anyone who wants to eliminate it can’t really define why they want to, because they just really don’t want their children to learn that there’s a reason we shouldn’t be racist towards people who are different from ourselves.

Amanda: Yeah, they want to uphold the secrets.

Clint: Yes, they don’t want anybody to know that there’s a reason that there are still people struggling in different racial groups. and are part of theirs. And there’s a reason, because it’s still been systemic the whole time. We are currently trying to erase square people in the state of Kansas completely. And there’s a very important need to kind of look at why and what it comes from, and then hold that hatred up to a light and see why. Because a lot of it here is, I can’t say it’s religious, because it’s really not. It’s just anger. And it’s a privilege under a mask.

Amanda: And fear.

Clint: And fear, yeah. The person who needs to walk around with a desert eagle strapped on their hip is far more afraid of everything out there than I am. The most dangerous thing I carry is a pen.

Amanda: Yeah, exactly.

Clint: It’s different than trying to capture a lovely image that says so much and someone would want it.

Amanda: Yeah, yeah. And it was just like, how am I… there’s just something so inherently fucked up about having to be competitive and this is what you’re competitive about. And it’s just, I hated it. I hated it so much. And I felt like a lot of people really just wanted to hear more because they were very interested in it, but without the intention of funding. I didn’t know the difference, so I was just kind of having to constantly do these pitches and share this over and over and over. And people would be like, oh my gosh, send us a rough cut. We want to see a rough cut. It’s just like, dude, I can’t even afford to do a four-minute cut. So yeah, it was really, I got very, very worn down and salty. It was really rough. And so I hit this point where it was like, I need somebody to come on board. And so we started looking for producers who knew how to make more money. That was like the only goal we needed. It was like, who can help us make money? And we got two grants the whole time, and they’re both British. They’re both British, which was interesting. And I don’t know how many scores of rejections I got from all the other ones. But really it’s given me some thick skin. Yeah, and so we met this production company, Arc Media. We met a producer, Rachel Drexan, who was recommended to us. And then she was like, oh, I’m with this production company. And we could do a shopping agreement with you and shop the film around. Because we already have the relationships with all these places and the reputation. I honestly didn’t know that could even work that way. I just thought I was in grant purgatory forever. Yeah, I mean they pitched it for a year, I agreed, and that was the first year of the pandemic, so that was like a really interesting, bizarre time. And I would say it landed on most places’ desks, and folks would say, no, or like, yeah, show us at Rough Cut. And then in the very last week of that agreement, we slid it over to HBO and it was truly the last swing. I was like if this doesn’t work, I don’t know what to do. Like, I might not make this, because I just don’t know what else to do. And… I, at the same time, because I couldn’t keep traveling, I moved back to the US to just take the leap. I was like, okay, well, I guess I’m just gonna move back and really try to finish this. And three days, I was in quarantine in Brooklyn, three days after I landed, HBO said yes. Yeah, you can only imagine. You can only imagine. So I was like, okay, I have made the right, the universe has said I’ve made the right decision. And, you know, but at the same time, you know, more money, more problems. Took six months to negotiate the contract, and then like, it would be done two years later after that, essentially. But it was so incredible. They were so wonderful to work with. They’re very filmmaker-friendly. I think we had like a handful of check-ins, but they didn’t tell me to do anything I didn’t want to do, and they really trusted me, and we kept delivering better cuts, and they were like, hey, just keep going. And so we really got to make the film that we wanted to make.

Clint: When does the doc drop on HBO? December 5th?

Amanda: December 5th.

Clint: Okay, everything just says late 2023?

Amanda: I assume there’s like a strategy. It’s just, they are so underwater right now. It’s very hard to get- every answer I get is so vague. So I’m just like, I’m just gonna do all my own fucking shit, and like…try and get some money out of them for all of this, because it benefits them too. I do see a lot of importance in this. I do see a lot of very, very necessary statements that aren’t being made.

Clint: They’re being made, but again, like you talked about, the grassroots movement of the VirtuPed side of it.

Amanda: Nah, yeah, yeah. Prevention issues at large, yeah.

Clint: But that’s all been a grassroots effort. It’s very much local, small things. There’s not been a national conversation about stigmatism, about, like… damage that we can cause by not acknowledging these things. So I do think you have made something very important.

Amanda: Thank you. Yeah, and I want to keep working on these things. Luke Malone, our producer, he’s writing a book about this that’ll come out in like a year or so, and that’s going to be really fantastic. And I think we’re getting closer to having these conversations. I think the film is coming at the right time. And even if it’s not about child sex abuse, it’s just family secrets. where people are projecting all kinds of stuff on it. And it’s just silence and the weight of that and how that gets passed on and impacts this generation.

Clint: What went wrong and what don’t we talk about?

Amanda: Yeah, yeah. It’s kind of a fill-in-the-blank film, at least I hope it is. And we’re releasing it in the holiday season. So very intentionally, I said, I want this out around Thanksgiving or Christmas.

Clint: It’s You and David Fincher’s The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, let’s just really swing with these dark films right around the holidays.

Amanda: I’m hoping that it catches like a zeitgeist-y moment and really gets people talking. I hope after that more people make things that have to do what I wanted this to and just keep continuing. I don’t want to co-opt the topic, I want the conversation to continue and I do have a lot of ideas of like little side projects. I’m not done talking about this. There’s not many people having this conversation. So like I’m happy to I’ve got the thing. People look at me…like, I’ve had people say, “I know you’re so fragile because of this, it’s like amazing how much people forget…“

Clint: How fragile can you be if you did this in the first place?

Amanda: Thank you. Thank you. It’s just interesting that people’s projections of like oh they can’t imagine doing something like this. But I feel like it’s weird because I was so normalized to it growing up that I don’t exist in the stigma. I can look at it quite clinically and I have the data, the firsthand experiences, and have seen how this isn’t dealt with.

Clint: I think every family has that one thing that they’re like wait that’s not normal when they finally get out into the world whether it’s you know my parents aren’t sure if we’re stopping at grandma’s today even if we’re already here because a relative is passed out naked in the front. yard and he’s probably not sure what he did last night. That’s totally not a specific memory or anything like that. That’s not a core memory at all. That doesn’t impact me greatly.

Amanda: Yeah, yeah, there’s stuff like that everybody has that they don’t talk about.

Clint: I think you’ve done an incredible job at saying, “Let’s talk about these things because acknowledging them is the only way we can change them.”

Amanda: Yes, and I don’t have the answers. But the first step is talking about it. And that’s all I want. If you take one thing away from this film, it’s just like the value of just saying these things takes the power away from them. And there are so many people just kind of isolated and suffering in silence.

Clint: America grows by inches, not feet, unfortunately.

Amanda: Yeah. So if I can just… I mean, there are some pretty heavy, big pills to swallow in this that not everyone’s gonna be on board. I’ve always operated thinking that if 30% of the people who see this start to question how they think they kind of like grasp this issue, then that’s a success.

Great Photo, Lovely Life premiers at 10pm on Dec 5th.