The return of Hayao Miyazaki came with some tenuous feelings, at least for me. His 2013 swan song The Wind Rises is about as perfect of a goodbye as one could ask for. The Boy and the Heron, announced under the title How Do You Live? after the 1937 Genzaburō Yoshino novel of the same name, garnered a lot of excitement as once again the world’s greatest animation director was making his “final film.” After its premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival, my spirits started to lift, and critics and Japanese audiences hailed it as a stunning statement from a director with a complicated relationship with his legacy.

It’s better than I could have ever hoped for.

And why shouldn’t it be? Hayao Miyazaki is an artist who has always surprised and, at least for me, always exceeded expectations. I first came to him in 2002 with the Disney clamshell release of his masterpiece, Spirited Away. Since then I’ve found my way to each subsequent release in time, never catching one at its theatrical release but always finding them eventually. The Boy and the Heron, perhaps a spiritual successor to Spirited Away, sits atop the heap as one of his greatest works. It serves as not only a farewell (even though he’s walked back his statement that it would be his final film) but also a look at his legacy, at his tumultuous friendships with the other Studio Ghibli founders, and at what he’s leaving behind. After viewing the film it’s not hard to see why he titled it How Do You Live?, a title that he aims directly at his children and grandchildren and wonders what they’ll think of his empire when he must leave this life.

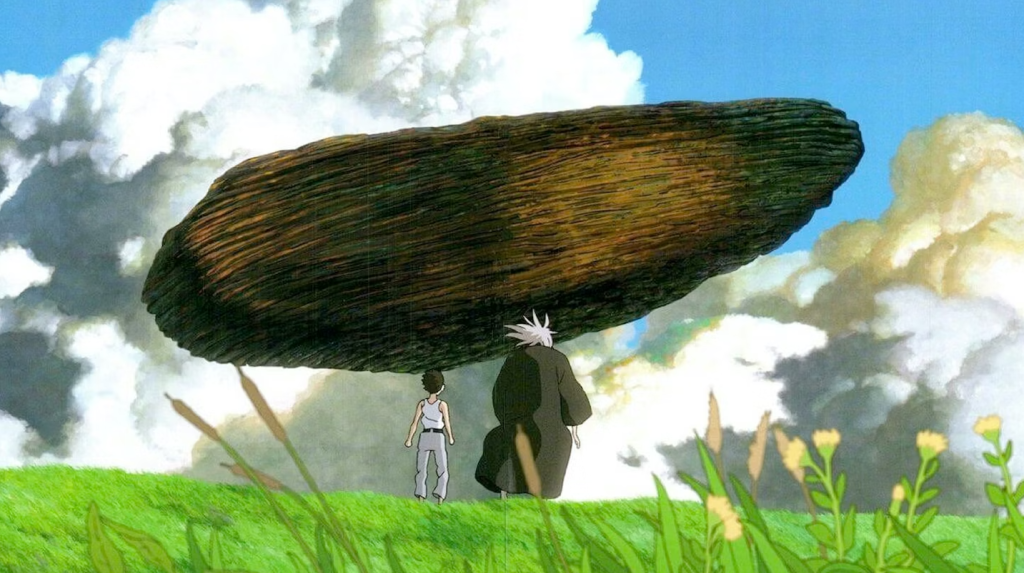

The story itself is something of an enigma, mystical and brutally savage while standing firm in its need to be more grounded than his prior works. Young Mahito (Soma Santoki, Luca Padovan in the English dub) has lost his mother. She burned to death in a hospital that caught fire in Tokyo during a WWII bombing. After a few years, his father Shoichi (Takuya Kimura, Christian Bale) marries his mother’s sister, Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura, Gemma Chan), who becomes pregnant and is desperate to take care of her sister’s family. Mahito is uncomfortable with all of this when they move to Natsuko’s countryside estate and his whole life is uprooted. He is stalked by a grey heron (Masaki Suda, Robert Pattinson), one that is up to no good, and on the eve of Natsuko’s disappearance stumbles into a world beyond life and death as he struggles to come to terms with his family, the future, and this really annoying heron that seems to be omnipresent.

It’s existential and heavy but The Boy and the Heron turns out to be perhaps his most contemplative, self-aware work. Mahito has a lot of the same traits as his creator, who lost his mother during WWII and moved to the countryside with his father. Mahito and Miyazaki both had to come of age in a time of turmoil and grief, having to learn to let go of the self and grow to a point where they could understand helping others. Mahito’s journey may be aided by a bunch of adorable grannies (one of which is voiced in a dual role by Ko Shibasaki and Florence Pugh), but his creator shows the boy little sympathy as he navigates his way from rage and self-affliction to savior.

While most English dubs are serviceable at best I do want to highlight this one for its excellence. Whereas most seem to not fully want to commit to the message, instead letting known Western actors put their own spin on the material, GKIDS Entertainment has gone to great lengths to create a wonderful experience that equals that of the film’s original voice cast. Studio Ghibli execs were invited to watch the film along with Western audiences, bemused and surprised by the reaction to the film’s humor when Japanese audiences were mostly stoic. They gave GKIDS more reign to play up the humor, cast as they thought best, and only left them a few notes. One of those notes? GKIDS wanted Danny DeVito to voice the heron, an obvious but probably correct line of thought that Ghibli rejected. They wanted someone hot, younger, and with a rockstar vibe. GKIDS brought in Robert Pattinson, who had been practicing voices on his own and recording them on his phone. What he brings to the role is truly staggering, unrecognizable, and fitting to the film’s material. The entire cast commits and preserves the spirit of their Japanese predecessors. Both recordings are incredible and I think that makes this a film to see at least twice.

The Boy and the Heron is a much different film than some of the more mainstream works of Miyazaki. There are the sweet, charming, and touching films like My Neighbor Totoro, Kiki’s Delivery Service, and Ponyo. His latest film feels more violent, more raw (a child bashes himself in the head with a rock, throwing a lot of what we see onscreen into ambiguity for parts of the runtime), and more in line with something like Princess Mononoke. Mahito is looking to slaughter this heron for the first hour of the film, learning to sharpen his knife and making himself a bow and arrow. The heron is a figure of malice in his eyes. Indeed, its first words to him feel cruel and mocking as he pretends to be Mahito’s mother and cries out for help. Mahito gets in fights at school and watches unborn spirits eaten by pelicans. Parakeets are apparently the most violent creatures on earth, at least according to this film. They serve as the antagonists, looking to eat humans, and are led by their king (Jun Kunimura, Dave Bautista) to try revolting against their master.

This spirit of death, birth, rebirth, and the violence surrounding existence is scored beautifully by Miyazaki regular Joe Hisaishi. Joining the director on his second film, Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind, the two have been inseparable since. For The Boy and the Heron, the team took a different approach to creating the music. Normally, Hisaishi would spend nearly two years on the score, take two off, and then begin working on the next film. There would be meetings and storyboards and material to work with but this time Miyazaki just let him do his thing. Within six months Hisaishi turned in the score and it is an all-timer. Hisaishi has composed some of the most beautiful film score tracks ever laid down and he has somehow still managed to make a series of tracks that move, sway with the wind, and tug at the heartstrings. If this turns out to be Miyazaki’s final film it will have been a truly masterful collaboration between two artists that seem to often bring out the best in each other.

While The Boy and the Heron may turn out to be Miyazaki’s last film it would be a fitting farewell. His vibrant emotions and clear unbridled creativity as he works through his own mortality have been laid bare, sometimes in ways that even he doesn’t completely understand. It’s a gorgeous final film, following yet another stunning final film. I don’t know what’s next but if he wants to release yet another goodbye I’ll be there to see him off.

The Boy and the Heron is now playing in theatres.

1 Comment